African Contemporary Art

African Contemporary Art: Nurturing Creativity and Shaping History As we unravel the narrative of...

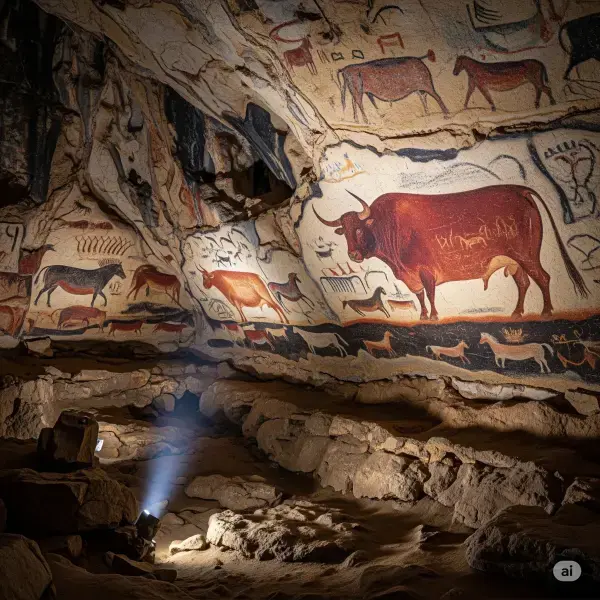

The Grotte de Lascaux in southwestern France stands as one of the most magnificent and well-preserved examples of prehistoric cave art in the world. Situated in the Vézère River valley near the town of Montignac in the Dordogne region, this cave complex is famous for its remarkable paintings and engravings created during the Upper Paleolithic period. Its discovery and study have profoundly influenced our understanding of early human creativity, culture, and symbolic thought.

In this article, we will explore the discovery of Lascaux, the nature of its artworks, the scientific dating and cultural context, the challenges of preserving such a fragile site, and how modern technology has helped make its wonders accessible without damage to the original cave.

The Lascaux cave was discovered accidentally on September 12, 1940, by four teenagers—Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas—while exploring the woods near Montignac. Their curiosity led them to uncover an opening to the underground chambers filled with astonishing images.

The news quickly reached Henri Breuil, a French archaeologist and preeminent specialist in prehistoric cave art, who visited the site soon after and recognized its immense importance. Breuil's studies helped bring international attention to Lascaux, establishing it as a vital source of knowledge about prehistoric humans.

The cave is a natural limestone cavern approximately 20 meters (66 feet) wide and 5 meters (16 feet) high. It consists of several chambers and corridors, including:

The Main Chamber or Nave

The Apse

The Axial Gallery

The Painted Gallery

The Shaft of the Dead Man

Each of these spaces is adorned with various paintings and engravings that decorate the walls and ceilings.

The artworks were created using natural pigments derived from minerals such as:

Red and yellow ochre (iron oxide-based pigments)

Charcoal (carbon black)

Manganese dioxide (black pigment)

The artists applied these pigments by brushing, spraying, and even blowing paint through hollow bones to create outlines and shading. Some figures were engraved directly into the stone surface, adding texture and depth.

The use of perspective, shading, and motion in these depictions is remarkable, revealing a sophisticated artistic understanding rarely attributed to prehistoric peoples.

Lascaux houses over 600 animal figures painted or engraved on its walls, including some of the largest known prehistoric animal images, along with nearly 1,500 inscriptions.

Some of the most notable figures include:

These large wild cattle are among the most dominant figures in the cave, with some painted nearly 5 meters (16 feet) in length. Their horns are drawn using a "wound perspective," where the horns appear twisted, indicating a conceptual rather than purely realistic style.

A mysterious two-horned animal often referred to as the "unicorn," although it is unlikely to represent a mythical creature. Some scholars speculate it may depict a composite or symbolic figure rather than a real animal.

Elaborate images of red deer are characterized by their detailed antlers, sometimes intertwined in complex compositions, highlighting the artists' attention to anatomy.

Numerous horses appear in various poses, some running, others standing. These portrayals capture the dynamism and diversity of the fauna known to the Paleolithic people.

Several stags appear with only their heads and necks painted, positioned over wavy lines interpreted as water, suggesting these animals are swimming.

A rare depiction of six cats, which may represent wild species like lynxes, emphasizes the diversity of animals portrayed.

Two male buffalo and various other creatures complete the rich fauna illustrated.

This enigmatic narrative scene shows a human figure lying on the ground, a wounded bison, a bird-headed figure, and a rhinoceros, among others. Interpretations vary widely, from a hunting accident to a shamanistic ritual, suggesting complex symbolic or spiritual meanings.

Radiocarbon dating places Lascaux's paintings at approximately 17,000 years ago, during the Magdalenian period of the Upper Paleolithic (roughly 17,000 to 12,000 years ago). This culture was characterized by advanced tools, bone and antler artistry, and complex social structures.

The purpose of the paintings remains debated, with theories ranging from:

Hunting magic: Belief that painting animals could increase hunting success.

Ritual or religious functions: Possibly shamanistic practices or spiritual ceremonies.

Communication or storytelling: Depicting narratives or important events.

The cave's art reflects a sophisticated understanding of animals, their behaviors, and perhaps their spiritual significance, revealing the cognitive and cultural complexity of prehistoric humans.

While radiocarbon dating of charcoal pigments provides an approximate age of 17,000 years, there is ongoing debate about the exact chronology of the cave's artwork. Some scholars argue that different chambers might have been painted at different times spanning several centuries or millennia.

More recent methods like Uranium-Thorium dating applied to calcite deposits overlying some paintings have provided additional constraints, but the overall dating remains complex due to the cave's layered use and environmental factors.

When Lascaux was opened to the public in 1948, its popularity quickly grew, with over 1,200 visitors per day at peak times. Unfortunately, human presence introduced several problems:

Increased CO₂ levels altered cave microclimate, affecting pigment stability.

Artificial lighting fostered the growth of algae and fungi on walls.

Physical disturbances including accidental touching or graffiti risked direct damage.

These factors led to the fading of pigments, formation of green algae, fungi, bacteria, and calcite deposits that obscured the paintings.

To protect the cave, the French government closed Lascaux to the public in 1963. Since then, extensive conservation efforts have been undertaken:

Controlling humidity and temperature inside the cave.

Eradicating biological growth with biocides.

Installing air filtration and monitoring systems.

Limiting access strictly to researchers and conservation staff.

Despite these measures, biological growth has recurred, including fungi and bacteria outbreaks noted as recently as 2001, requiring continuous monitoring and intervention.

To balance public interest and preservation, Lascaux II was opened in 1983. This replica is located a few hundred meters from the original and reproduces the most famous sections of the cave with astonishing accuracy, including textures, colors, and scale.

Further advancements led to:

Lascaux III: A traveling exhibition showcasing parts of the cave art worldwide.

Lascaux IV: Opened in 2016, a state-of-the-art interpretive center using immersive multimedia technology to educate visitors about the art, culture, and conservation efforts surrounding Lascaux.

These initiatives have helped preserve the original cave while making its wonders accessible to millions.

Lascaux remains a cornerstone in the study of prehistoric art and human evolution. Its discovery reshaped our understanding of early humans as not only survivors but also artists and symbolic thinkers capable of abstract representation and cultural expression.

Lascaux’s influence extends beyond archaeology into modern art, inspiring 20th-century artists such as Picasso and Matisse, who admired the power and simplicity of prehistoric images.

Current research at Lascaux involves:

Advanced imaging and non-invasive analysis to study pigments and painting techniques.

DNA and microbiological studies to understand microbial threats.

Archaeological excavations around the site to uncover more about the people who created the art.

The French Grotte de Lascaux stands as an extraordinary testament to human creativity nearly 20,000 years ago. From its stunning animal paintings and enigmatic scenes to the modern challenges of preserving such a delicate heritage, Lascaux continues to captivate scholars and visitors alike.

Its discovery provided a vivid connection to our distant ancestors, reminding us that the urge to create, tell stories, and seek meaning is a fundamental part of the human experience that transcends time.

Comments